Graham Barton, Academic Support Coordinator and Judy Willcocks, Head of Museum and Study Collection at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

This article reflects on the coming together of two pedagogic practices – museological teaching practice and learning development – to develop a form of object-based self-enquiry. This teaching practice has emerged from a shared practitioner interest in the use of museum and special collection objects as mediating artefacts (Vygotsky, 1978; Engeström, 1999) for increasing learning awareness. It considers the design and development of workshops which use museum objects as a focus for surfacing student self-perception of the role of values, assumptions and habits of mind in meaningful learning, particularly where these become influenced by disciplinary ways of thinking and practicing.

object-based learning; learning awareness; self-enquiry; transdisciplinarity

This article shares a transdisciplinary methodology for learning development practice, which draws on the use of objects from special collections currently held within the University of the Arts London (UAL). During the past three years, teams working with special collections at each of UAL’s colleges have teamed up with the University’s Academic Support department, resulting in the development of an interdisciplinary pedagogic approach to learning development: object-based self-enquiry.

Drawing on examples from the authors’ experiences, this article focuses on work which has taken place in an accredited museum, and is framed by literature on object-based and transformative learning. It argues that the assumed ‘specialness’ of museum objects allows multidisciplinary groups of all levels of study to explore personal learning habits, attitudes and preferences through mediating objects. The data referred to in this article has been gathered through structured observations, student feedback forms and semi-structured interviews with students who participated in the series of workshops.

UAL describes itself as Europe’s largest specialist arts and design university, with close to 19,000 students who come from all over the world to study in one of the University’s six colleges – Camberwell College of Arts, Central Saint Martins, Chelsea College of Arts, London College of Communication, London College of Fashion and Wimbledon College of Arts. The University offers an extensive range of courses in art, design, fashion, communication and performing arts.

UAL’s Academic Support department provides extra teaching, enhancement activities and resources to help students improve in areas such as learning approaches, creative academic practices, academic literacies, research and collaboration skills. An important strand of the Academic Support remit is to help students look at learning and studying as practices alongside or interwoven with creative practice. One of the key dimensions of the University-wide Academic Support on offer is to provide spaces for students to experience ways to understand personal learning habits and approaches to decision-making processes in creative academic study. However, the cross-University Academic Support team is small and consequently, has grown the offer through collaboration with other departments, through both open events and through resources published on the Academic Support online portal. One such collaboration has been with the Museum & Study Collection at Central Saint Martins (CSM).

The CSM Museum & Study Collection is an Accredited museum comprising over 25,000 objects, books and periodicals relating to the disciplines of art and design. The Collection originated in the late nineteenth century and has continued to grow ever since. Initially, items of general interest – such as illuminated manuscripts, rare books and film posters – were collected, but since the late 1980s the museum has principally collected work by staff, students and alumni. As an Accredited museum, there are limitations on the way objects can be used, but the intention remains that the collection should be used to support teaching and learning across UAL. With creative thinking and sensible frameworks for protecting the objects in place, there is much the Museum & Study Collection can offer in terms of teaching and learning support.

The collaboration between the CSM Museum & Study Collection and the Academic Support team drew together two different but aligned practices, providing a forum for experimentation and iterative development of teaching practice in direct response to student feedback and structured research.

The collaboration arose from a combination of motivations. With the appointment of a new university-wide Associate Dean of Academic Support and a new Academic Co-ordinator, the Academic Support team was tasked with extending the remit of learning development into new areas. These include the development of student awareness of learning processes and purposes, recognition of habits of mind and frames of reference, as well as decision-making processes and understandings of creative academic study practices. At the same time the Museum & Study Collection was thinking strategically about how to use its collections to better support teaching and learning across the university and working to develop its understanding and practice around object-based learning.

Objects are the ‘inscribed signs of cultural identity’ (Hooper-Greenhill, 2002, p.11). They can act as powerful metaphors, enabling abstract ideas to be communicated and understood. Since the late 1980s, museums in the UK have been moving away from a more traditional model of curatorial practice where expert curators were expected to share their knowledge with a predominantly passive audience. The grand curatorial narrative has given way to the idea of personal and collaborative meaning making, placing more importance on what the visitor brings to an understanding of museum objects, and accepting the capacity of objects to have multiple meanings (Hooper-Greenhill, 2002).

While many disciplines use objects in pedagogic practice, the term ‘object-based learning’ was coined by Paris (2002) in response to an increased emphasis on student centred learning in museums and a consequent reconsideration of museum objects within the frameworks offered by educational theory. UCL Museums have led the field of enquiry into this area of pedagogic practice in terms of codifying and articulating what this might mean in the context of higher education (Chatterjee et al., 2008; Duhs, 2010; Chatterjee and Hannan, 2015).

For Paris it is the ‘transaction between object and person that evokes and allows meaning construction’ (2002, p.xv). Consequently, museological practice should allow museum visitors to draw on their prior knowledge and experience – what Bordieu would call ‘cultural capital’ (Bordieu, 1986). Simon describes a new breed of ‘participatory’ museum, which seeks not to deliver the same content to all, but to ‘share diverse, personalised and changing content co-produced with visitors’ (2010, p.iii). This model assumes an equitable partnership between curator/educator and museum visitor, where the end users are also seen as the content creators. Simon argues that the best participatory experiences are carefully managed to ensure a positive visitor experience.

The last two decades have also seen equality and diversity moving from the margins to the core of museum practice (Sandell and Nightingale, 2012, p.1), with curatorial processes seeking to represent a much broader spectrum of lived experience. Museums are increasingly seen as ‘safe spaces’ to challenge accepted narratives and ‘nurture respect for cultural differences’ (Bodo, 2012, p.181). Within this context, objects have the potential to become a positive focal point for exploring cultural, social or disciplinary viewpoints. As Simon describes, objects ‘allow people to focus their attention on a third thing rather than each other’ (2010, p.127). It is this capacity to spark conversation and focus attention on a point beyond the user which makes object-based learning such a useful tool for working with diverse audiences.

The main aim of the Museum & Study Collection at CSM is to support teaching and learning within an art and design environment, providing students with the skills to engage with objects physically and intellectually and to conceptualise and contextualise ‘beyond the object’ (Cook, 2010, p.94). With only a small permanent display space, the Museum & Study Collection must work creatively, as a handling collection, delivering sessions for small numbers of users. Handling sessions are structured to explore both personal meaning making and the dynamics of collaborative meaning making, where groups of students work with and against objects to co-construct a narrative (Paris, 2002, p.227). Prior to the collaboration with Academic Support, sessions were in the main delivered to single course groups, though interdisciplinary sessions were delivered for external audiences and through the college’s widening participation programme.

Although many objects in museums were made to be touched, held or worn by people (Spence and Gallace, 2008, p.33) much recent writing on object-based learning in museums still assumes that the prevailing paradigm sanctions against touch (Willcocks, 2015, p.47). However, Hooper-Greenhill suggests that ‘it is through embodied interpretation that objects become meaningful’ and argues that much of the way objects are understood by those who engage with them is tacit, not articulated or even acknowledged (2002, p.116). The professional practice of the Museum & Study Collection has been developed to explore and foreground those tacit responses through haptic engagement with collections which help the learner to ‘develop a deeper awareness of his or her own beliefs, assumptions, stereotypes, and realise that many meanings are both possible and legitimate’ (Paris, 2002, p.230).

Another key strand of the Museum & Study Collection’s work is researching the student experience of object engagements to help inform and improve the service it offers. University-based museums are in a unique position to combine professional practice with academic research, and the Head of Museum at the CSM Museum & Study Collection is also a Senior Research Fellow. Working in conjunction with UCL Museums, this research seeks to identify what haptic based object encounters mean for cognition, memory and understanding within an art school environment.

Learning development (LD) emerged broadly from study skills teaching in the 1990s, but was then transformed, perhaps most influentially via academic literacies, as a field of research and enquiry (Lea and Street, 1998; 2006; Lillis and Scott, 2007). While still maintaining an emphasis on study support, LD has subsequently evolved as a pedagogic practice concerned with enabling students to engage meaningfully with, enquire into and develop critical participation and agency in academic practices (Hilsdon, 2010).

Alongside student enquiry-led approaches to the development of study skills, capacities, capabilities and competences, analysis of ‘self-response’ is important. This is a way of ensuring that learners are aware of how habits of mind, frames of reference and thinking patterns are congruent (or otherwise) with skilful academic responses in various contexts. While much learning development and academic support work focuses on developing students’ writing and related academic literacies (Winter, Barton, Allison and Cotton, 2015), student critical and participatory engagement with the ‘academic’ can be enhanced through teaching practices that seek to develop a wide range of inter-related cognitive processes and literacies. Skills-focused approaches, developing a range of student literacies such as academic writing and critical thinking, can be enhanced through an emphasis on metacognition or self-awareness, what we are referring to broadly as epistemic and systemic cognition. In arts education, the latter is often perceived as contextual thinking, or relational and situational awareness – particularly cultural awareness – while the term ‘epistemic’ is used here to refer to the knowledges and systems of ideas developed over time within a discipline, subject or practice area. Attention to these dimensions of cognition, as well as to visual perception and material sensibilities, are often taught or cultivated through a range of signature pedagogies (Shreeve, Sims and Trowler, 2010). This confluence of pedagogies and approaches helps to engage students more deeply with the academic literacies required for academic study as social practice, and with study and learning-as-practice ‘interwoven’ with creative practice.

The viewpoint of study-as-practice is important to the approach to academic support at UAL, as it affords a conceptual space that allows not only for ‘functional’ and process-driven dimensions of academic study, but also critical and participatory approaches to developing students’ creative practices (including the notion of ‘academic’ as creative practice). This view has led to a drive to raise awareness in learners of their own critical thinking approaches, alongside an engagement with affective and extra-rational dimensions of learning, echoing Barnett’s ‘pedagogy of human being’ (2004). Such approaches also align with pedagogic practice in ‘Education for Sustainability’, with its emphasis on the importance of systemic and epistemic cognition for transformational learning (Sterling, 2010-11; Bateson, 1972). Winter et al. (2015) propose that LD is concerned not only with helping students to learn to learn, but also learn about learning and to learn how to learn about learning (Bawden, 2005), enabling them to develop awareness of the contexts in which learning takes place. This echoes other transformational learning literature, for example Perkins points to the importance of cultivating a contextual view of the system of ideas within disciplines: ‘many students never get the hang of it, or only slowly, because the epistemes receive little attention’ (2006, p.43).

As touched on by the perspectives outlined above, one of the central assumptions of learning development is that learning is often more than the simple acquisition of new knowledge and skills, with the potential for transformations in perceptions, values and beliefs. This concept, known as ‘transformative learning’ has been well theorised in literature relating to higher education and is usually attributed to the educational research of Mezirow (1991) and earlier theorists such as Bateson (1972). It is succinctly described by Illeris as ‘learning that entails a qualitatively new structure or other capacity within the learner’ (2014, p.5). As Illeris argues, in a rapidly changing world ‘the development of strong self-perception and confidence’ becomes an increasingly important factor in transformative learning (2014, p.1).

Alongside the importance of self-perception and confidence in arts and design education, transformative learning (in the wider context of transformative education) has been identified as one of the key strands of University-wide teaching and learning at UAL. When collaborating on the construction of the workshops described in this article, one of the main concerns was to ensure that an environment was created where transformative learning experiences had the potential to flourish – where students would feel comfortable enough to challenge their own habits of mind and frames of reference through critical self-reflection and dialogue with peers, and also undertake enquiry into the social and institutional influences on their learning and creative practice.

Mezirow (1991) argues that such transformations and progression require the catalyst of a disorienting dilemma, followed by rational discourse and critical reflection on that dilemma. In turn, such processes of self-reflection and enquiry require mediation, variation and multiplicity, and we drew upon these conceptions to employ the object as a mediating artefact (Vygotsky, 1978; Engeström, 1999) for understanding individual ways of thinking and practising. In bringing together two practices – museological and learning development – workshops were designed to help students engage critically with academic practices (troublesome or otherwise) in their discipline, with the aim of creating affective and extra-rational dimensions of learning within and beyond the curriculum. The workshops intended to provide dis/orienting experiences with a focus on self-awareness.

Collaboratively run by Museum & Study Collection and Academic Support staff and drawing on the experience and practices of both, workshops typically lasted between 2 and 3 hours. Sessions were limited to 15 students, to reflect the fact that students were handling real (and in some instances rare or precious) museum objects and to ensure that each student received the attention and support they need. Workshops were advertised in advance and participants from all areas of the University, from Foundation to Postgraduate level, signed up through Academic Support online. Hence, each workshop involved a range of students from a variety of disciplines and levels of study.

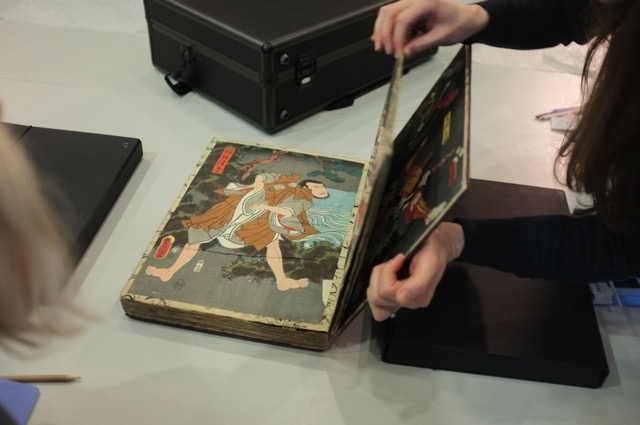

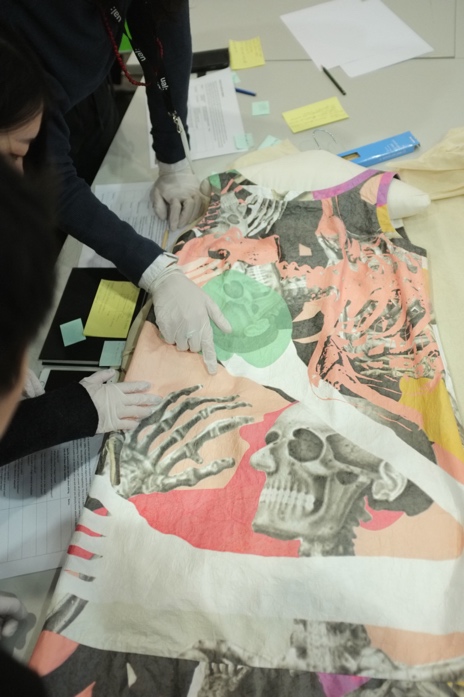

In terms of their structure, the workshops open with participants being invited to introduce themselves and describe what they are hoping to get from the session. Following these introductions, participants are given a set of handling instructions, which ensure the safety of the objects involved. These might include washing hands, wearing gloves, using supporting props or cushions and working slowly and methodically. A large object, big enough for the whole group to work with, will already have been chosen for the initial object enquiry. However, objects for subsequent activities will then be selected in response to the students’ interests and needs.

Many of the students already had some degree of object literacy. However, the focus of these workshops is not primarily the promotion of an understanding of materiality or material culture but to encourage students to become more aware of how their background and disciplinary viewpoint drives their thinking – habituated responses in context. To create an environment where those sorts of personal revelations might take place, it is assumed that there are no ‘experts’ in the room and that every voice carries equal weight.

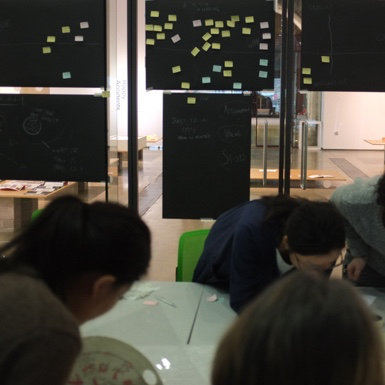

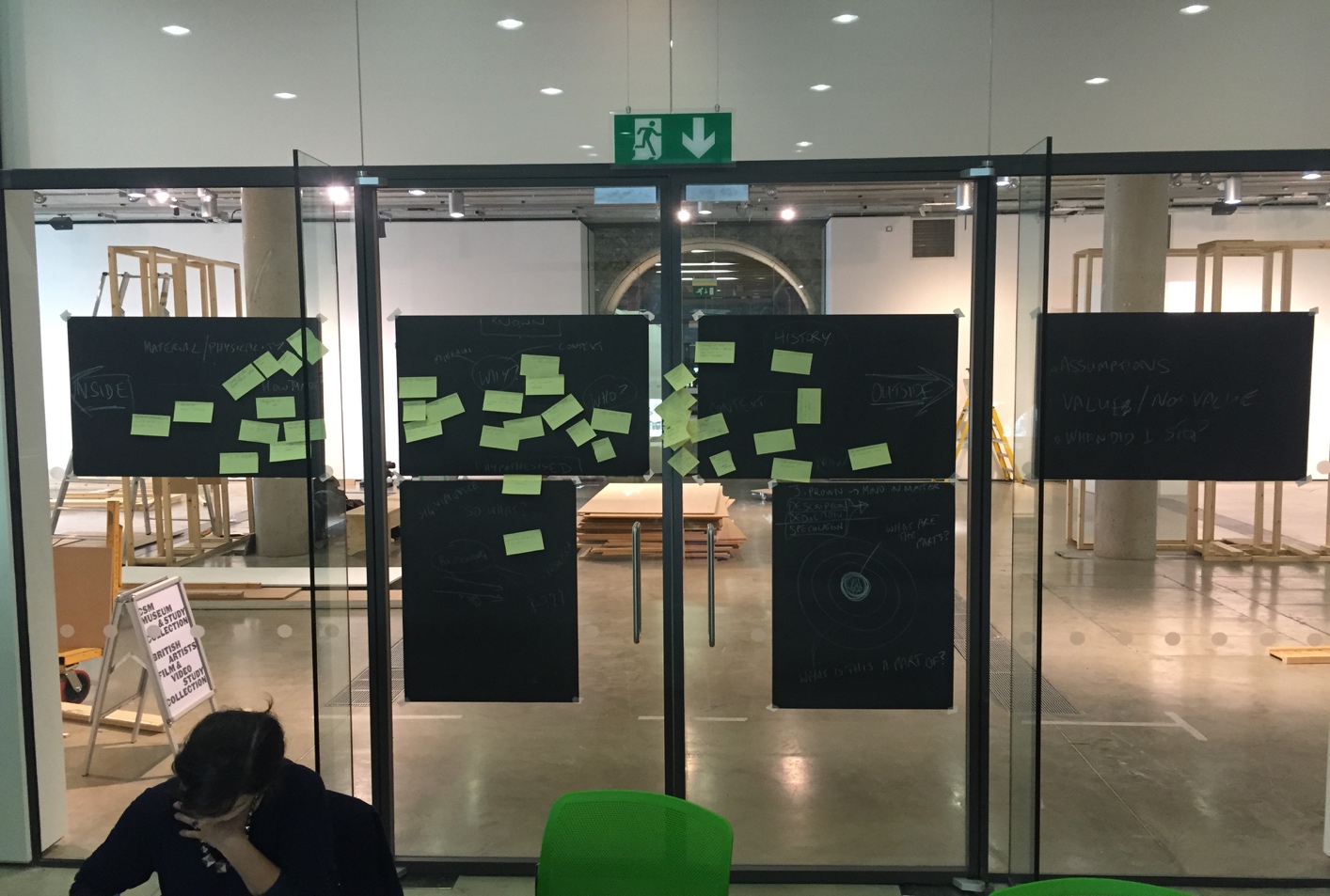

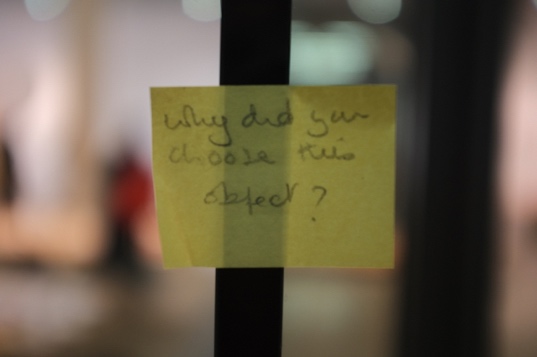

The initial activity is introduced not as a competition to see who can deduce the most about the object, but instead to elicit awareness of habits of mind and systemic context. Students are asked to list the questions they are asking of the object, rather than any hypotheses or assumptions they are making about materiality, context or origin. The group then works together to classify the questions, from the material and physical to the contextual and hypothetical – this is framed simply as a continuum from ‘Inside’ to the left and ‘Outside’ to the right (figure 10). The ‘Inside’ end of the continuum refers to questions that relate to the physicality and materiality of the object, while ‘Outside’ refers to contextual questions. Participants also explore their questions in terms of what they might be able to answer by looking closely at the object and what they can only guess at; this emphasizes that certain questions will create leading questions, for example ‘Is it a …?’ is often as leading as a propositional statement.

The aim of this initial activity is to examine the nature of such questions within the context of logical reasoning and affective responses and to explore what is assumed, and what is tacit and therefore unarticulated. Some disciplines or subject areas seem to influence participants to adopt systemic or analytical reasoning and certain forms of questioning as habituated responses. Notwithstanding the generalisation, Fine Art students often write questions that relate to an artist’s intentions at the time the work was created, while students with art historical or curatorial practices often note a range of questions that relate to the presence of the artefact within the museum/collection itself. Through analysing the placement of questions, students are provided with a context for examining the nature of analytic and systemic reasoning and crucially, the way in which their discipline or subject area is encouraging them to prioritise certain responses to phenomenon and the artefacts they encounter.

Following discussion and analysis of questioning habits, students are then introduced to a range of models for object analysis. The selection of objects used in this section of the workshop will depend on each group of students, their disciplines and interests. The nature of the object engagement is similarly tailored to the group’s requirements and can include:

Whatever the emphasis, it is central to the process that students spend a considerable amount of time with the object they are working with. Each object engagement typically lasts for at least half an hour, including discussion time, and close study of the object is encouraged. Ideally each handling session will allow for two object engagements following the initial ‘questioning’ round. However, students often become so immersed in their engagement with the object there is only time for one.

Methodologies are employed to support students in a forensic study of the object. These include:

The development of the workshops drew in part on ‘phenomenographic’ conceptions of enquiry into group participation (Marton, 1986), where the variation in experience is the point of study, or the point of intended learning gain and enquiry. This approach may account for the successful merging of different students from different levels of study, and from different subject areas, allowing workshops to explore the variation in each student’s responses to the object or artefact. There was initially some concern that variations in material culture awareness might be problematic, but because the focus is on an individual’s response – not the reading of the material culture – this has not proven to be the case. Who can guess the ‘right’ answer or know the most about an object’s context was not central to the workshops. Rather, they considered each individual’s personal response and what may be driving that as the generative focus.

Of further note was the way in which, and when, participants from different disciplines valued the object or, at times, disengaged from it. As a way of identifying these moments, during readings the participants are interrupted with a series of questions, such as what is your individual response, and what is driving that response? Are these habits of mind/usual responses for you? What you value and not value? At what stage of the reading did you stop? By doing this as a group – alongside other participants from different subject areas and differences – the workshops began to surface variation in experience, similar to the outcomes of phenomenographic action research (Marton, 1986).

During the workshops students often spent time working in small groups of three or four, contemplating an object and sharing their thoughts, responses and ideas. The groups then fed back to one another, explaining what they saw or discovered, what they learned about their own knowledge, understanding and attitudes, and what they chose to assume or ignore about the object. From an academic literacies perspective, this approach enables a degree of learner autonomy and agency; rather than being assessed on a person’s ability to apply a model for reading an object, the formative assessment in the workshop is self-directed, surfacing awareness of where choices of approach are acknowledged, valued and appraised. In parallel, within the context of museological educational practice, this way of approaching museum objects, with the focus on what the viewer brings to the object in terms of knowledge and experience rather than curatorial interpretation or meta-narrative, disrupts the traditional power relationship between the museum and the museum visitor.

Reading anything and trying to figure out what it is can be an individualistic and closed experienced, so it is wonderful to be able to collaborate and hear different perspectives and accept other people's viewpoints.

(workshop participant feedback, 2015)

As a result of the multi-disciplinary groupings, further insights into the ways different disciplines see or question objects emerged. For example, fine artists may seek meaning in colour and form where fashion history curators may want to know what the object tells us about societal preoccupations. Different kinds of makers have different knowledges of material processes or social contexts. In-depth interdisciplinary study of objects with which the students are not familiar creates a collaborative encounter that is held in a space of collective enquiry rather than a competitive ‘banking’ approach to knowledge about those objects. In working with an object they have never seen before, students are forced to activate prior knowledge in terms of disciplinary frameworks, historical context and materials. In this context, the knowledge and experience of a foundation level student is as important, beneficial and relevant as that of an MA or PhD student. As one remarked, ‘I kind of see this space as a safe space where I'm allowed to go beyond my normal kind of thinking.’ (workshop participant feedback, 2015).

To enhance the development of metacognitive awareness, other key questions asked of students in the sessions included:

Watching students approach objects from different angles and pool their knowledge to co-produce a new understanding makes manifest Kolb’s assertion that the pursuit of knowledge is a communal activity (1984). Peer-to-peer learning is an important aspect of art and design pedagogy so bringing that into the museum environment helps the students to be more engaged with the learning experience. As they compare their personal preoccupations and interests (perhaps around materials or construction) with those of others (say the historical or social context of the object) new meanings around the objects emerge. In addition to showing respect for the students and what they already know (Biggs and Tang, 2011) this can also help to surface the students’ own learning preferences.

During the past three years, these sessions have been successfully delivered to cross-college multidisciplinary groups from both undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Students have reported that they value the different ‘readings’ of objects undertaken by peers, and have learnt or extended their range of methodologies for object-based enquiry and approaches to questioning as a result. Most insight and awareness emerges in accordance with the group – their level, language skills and disciplinary mix, and it is unrealistic to expect groups to achieve an understanding of all areas in every session. However, feedback from evaluations indicates that at least some students within each group undergo a learning experience that has encouraged them to see anew:

‘It was surprising how different people from different areas had different ways of analysing an object.’

‘Made me curious about all the other perspectives from people.’

‘You have to switch on this sort of sensitive thinking.’

‘The session awakened my questioning and curiosity.’

‘My collaborative thinking has become more effective.’

(workshop participant feedback comments, 2015/2016)

The evaluations above came from a variety of sources, including reflection sheets on the workshops, a follow-up focus group session and extensive evaluations and research-based observations of object-based learning practice. At the informal end, these were standard end-of-session evaluation sheets, anonymised and handed out to workshop participants five minutes before the end of each session. At the more formal end, the student focus group included the use of ethics approval and consent forms and participant information sheets, developed by following guidelines stipulated by the British Educational Research Association (2011). To gain information on the benefits of object-based learning, the Museum & Study Collection used a questionnaire developed by University College London, UCL Museums, as the basis for its research and added several questions to explore the resonance of object-based learning for art and design pedagogy. The questionnaire was approved by the ethics teams at UAL and UCL and began with a short statement explaining the nature of the research and how data would be used and stored. Those taking part in focus groups were given a more in-depth précis of the project and sent transcripts of the workshops for approval.

As an Accredited institution, the Museum & Study Collection abides by the same rules and regulations that govern any other museum in the UK: according to which a museum’s primary concern must always be the long term preservation of the objects in its care. There are a number of ways of ensuring that museum collections can be handled safely by visitors, including limiting group sizes to 15, giving clear handling instructions, supervising all handling and insisting that visitors wash their hands. Records of the number of times an object is shown are kept to mitigate against over-showing or over-handling and are regularly checked for degradation. If all these measures are in place, the risk to collections is minimal.

Objects selected for the workshops are generally reasonably robust, and for the workshops to be successful the objects must also pose questions or act as a physical provocation. Objects chosen to date include a fifteenth century book of church music from Bologna in Italy, an early twenty first century woven bamboo chair, a late twentieth century pair of leather thong pants with masonry nails by fashion designer Andrew Groves, items from personal wardrobe of Saville Row tailor Hardy Amies (Figure 7), a pair of gentleman’s dress shoes (Figure 3), a tongue-in-cheek hamster cage with shredder powered by the hamster wheel and an early nineteenth century fabric scrap book from Lyon in France (Figure 1). These objects allow for detective work or hypothesis around a provocation.

The question has been raised as to whether these workshops could be delivered with ‘any old objects’ and technically the answer is yes. The classroom or studio could be ransacked for stained coffee mugs, tools or furniture and students asked to engage in an object enquiry. Students bringing in personal objects that have significance to them is also a tried-and-tested method in English language communication classes. However, museum collections are distinct in that their objects have an assumed additional cultural value either through their uniqueness or their antiquity – what Benjamin would call their ‘aura’ (1999).

Evans and Mull suggest that museum practice is driven by the assumption that it’s the ‘authenticity and uniqueness of the museum-based objects that summons the most powerful reactions’ (2002, p.55). Illeris (2014) argues that it is most often the emotions that make learners question their central assumptions and beliefs and there seems to be something about the sense of awe and privilege that lifts the students out of themselves and facilitates discussions between widely different age groups. It is not unusual to have a PhD student engaging in lively conversation with a student on a Foundation course over an early nineteenth century scrap book in a way which would be unconceivable over a stapler. Drawing on the experience of these sessions, the authors propose that the assumed ‘specialness’ of museum objects allows multi-disciplinary groups of all levels of study, to explore both objects and personal learning dispositions within an inclusive pedagogic environment.

The emergent pedagogy of ‘object-based self-enquiry’ is the result of two fields of practice with significant alignment between them – learning development and museology – collaborating to support and enhance learning opportunities for art and design students. In object-based self-enquiry, archival and museum objects are used as mediators or mediating artefacts (Vygotsky, 1978; Engeström, 1999) for engaging in learning and self-awareness. Rather than focusing on how to read or analyse objects for curriculum purposes, the approaches outlined above have emphasized the value of using museum artefacts for non-judgmental analysis of habits of mind and evaluating personal and collective disciplinary responses. Early evaluation of object-based self-enquiry reveals how participants become more aware of their own learning processes and purposes through such approaches. It also shows where their responses to objects lie in relationship to developing analytical, systemic and epistemic cognition, as well as developing visual perception and material sensibilities. The approaches outlined in this article appear to have value for developing approaches to helping students perceive study and learning as creative practices, for increasing the understanding of difference, synergies and intersectionalities and for developing the awareness and reflection necessary for transformative learning.

Arnheim, R. (1969) Visual thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Barnett, R. (2004) ‘Learning for an uncertain future’, Higher Education Research and Development, 23 (3), pp.247-260.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps Into an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine.

Baudrillard, J. (1968/1996) The system of objects. London: Verso.

Bawden, R. (2005). ‘Systemic development at Hawkesbury: some personal lessons from experience’, Systems Research and Behavioural Science, 22(2), pp. 151-164.

Benjamin, W. (1935) ‘The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’ in Arendt, H. (ed.) (1999) Illuminations. Translated by Harry Zohn. London: Pimlico, pp.211-244.

Biggs, J.B. and Tang, C.S. (2011) Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does. 4th edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Bodo, S. (2012) ‘Museums as intercultural spaces’ in Sandell, R. and Nightingale, E. (eds.) Museums, equality and social justice. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.181–192.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The Forms of Capital’. In Richardson, J. (ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood Press, pp. 241-258.

British Educational Research Association (2011) Ethical guidelines for educational research. London: BERA. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-2011.pdf (Accessed: 24 June 2017).

Chatterjee, H., Duhs, R. and Hannan, L. (2013) ‘Object-based learning: a powerful pedagogy for higher education’ in Boddington, A., Boys, J. and Speight, C. (eds.) Museums and higher education working together: challenges and opportunities. Ashgate: Ashgate Publishing, pp.159–168.

Chatterjee, H., MacDonald, S., Prytherch, D. and Nobe, G. (2008) Touch in museums: policy and practice in object handling. New York: Berg.

Cook, B. (2010) ‘The design student experience in the museum’ in Cook, B., Reynolds, R. and Speight, C. (eds.) Museums and design education: looking to learn, learning to see. Ashgate: Ashgate Publishing, pp.91–104.

Dierking, L.D. and Falk, J.H. (2000) Learning from museums: visitor experiences and the making of meaning. Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

Duhs, R. (2010) ‘Learning from university museums and collections in higher education’. (From Putting university collections to work in teaching and research: proceedings of the 9th conference of the International Committee of ICOM for University Museums and Collections (UMAC), Berkeley, USA, 10th–13th September 2009), Universities, Museums and Collections Journal, (3), pp.183–186.

Engeström, Y. (1999) ‘Activity theory and individual and social transformation’ in Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R. and Punamäki, R.L. (eds.) Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.19–38.

Gallace, A. and Spence, C. (2008) ‘A memory for touch: the cognitive psychology of tactile memory’ in Chatterjee, H. (ed.) Touch in museums: policy and practice in object handling. New York: Berg, pp.163–186.

Hilsdon, J. (2010) ‘What is learning development’ in Hartley, P., Hilsdon, J., Keenan, C., Sinfield, S. and Verity, M. (eds.) Learning development in higher education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2002) Museums and the interpretation of visual culture. New York: Routledge.

Houson, A. (2002) ‘Aesthetic thought, critical thinking and transfer’, Arts and Learning Research Journal, 18(1), pp.99–132.

Illeris, K. (2014) Transformative learning and identity. London, Routledge.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V. (2006) ‘The “academic literacies” model: theory and applications’, Theory into Practice, 45(4), pp.368–377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11.

Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V. (1998) ‘Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach’, Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), pp.157–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364.

Lillis, T. and Scott, M. (2007) ‘Defining academic literacies research: issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy’, Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), pp.5–32. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v4i1.5.

Marton, F. (1986) ‘Phenomenography – a research approach investigating different understandings of reality’, Journal of Thought, 21(2), pp.28–49.

Mezirow, J. (1991) Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Paris, S.G. (2002) Perspectives on object-centred learning in Museums. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Peirce, C.S. (1991) Peirce on signs: Writings on semiotic. Edited by James Hoopes. London/Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Books.

Perkins, D. (2006) ‘Constructivism and Troublesome Knowledge’, in Land, R. (2006) Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge.

Prown, J. (1982) ‘Mind in matter: an introduction to material culture theory and method’, Winterthur Portfolio, 17(1), pp.1–19. https://doi.org/10.1086/496065.

Rowe, S. (2002) ‘The role of objects in active, distributed meaning making’, in Paris, S.G. (ed.) Perspectives on object-centred learning in museums. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge, pp.19–36.

Ryan, P.J. (2009) Peirce’s semeiotic and the implications for Aesthetics in the visual arts: a study of the sketchbook and its positions in the hierarchies of making, collecting and exhibiting. London: Wimbledon College of Art, University of the Arts London. Available at: http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/5252/ (Accessed: 27 June 2017).

Sandell, R. and Nightingale, E. (2012) Museums, equality and social justice. Abingdon: Routledge.

Shreeve, A., Sims, E. and Trowler, P. (2010) ‘A kind of exchange: learning from art and design teaching’, Higher Education Research and Development, 29(2), pp.125–138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360903384269.

Simon, N. (2010) The participatory museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

Spence, C. and Gallace, A. (2008) ‘Making sense of touch’ in Chatterjee, H. (ed.) Touch in museums: policy and practice in object handling. New York: Berg, pp.21–40.

Steele, V. (1998) ‘A museum of fashion is more than a clothes-bag’, Fashion Theory, 2(4), pp.327–335. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/136270498779476109.

Sterling, S. (2010-11) ‘Transformative learning and sustainability: sketching the conceptual ground', Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 5, pp. 17-33.

Wenger, E. (1999) Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yenawine, P. (1999) ‘Theory into practice: the visual thinking strategies’, Aesthetics and art education: a transdisciplinary approach. Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal, 27–19 September. Available at: https://vtshome.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/9Theory-into-Practice.pdf (Accessed: 27 June 2017).

Youngman, M.B. (1982) Designing and analysing questionnaires: rediguide number 12. Oxford: TRC-Rediguides Ltd.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Edited by Michael Cole, Vera John-Steiner, Sylvia Scribner and Ellen Souberman. Translated by J.V. Wertsch. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Willcocks, J. (2015) ‘The power of concrete experience: museum collections, touch and meaning-making in art and design pedagogy’ in Chatterjee, H. and Hannan, L. (eds.) Engaging the senses: object-based learning in higher education. Farnham: Routledge, pp.43–56.

Winter, J., Barton, G., Allison, J. and Cotton, D. (2015) ‘Learning Development and Education for Sustainability: what are the links?’ Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education Vol. 1(8). Available at: http://www.aldinhe.ac.uk/ojs/index.php?journal=jldhe&page=article&op=view&path%5B%5D=256 (Accessed 16 July 2017)

Following an early career in commercial property as a Chartered Surveyor, Graham Barton switched to parallel careers in performing arts, as a musician/sound designer/producer, and Higher Education, in the latter specialising in English for Academic Purposes and Learning Development. His educational interests have emerged from these personal and professional changes, and from finding ways to draw on educational theories as vehicles to help learners engage with transformative learning. Areas of pedagogic research interest include academic study as creative practice, contemplative practices for self-enquiry in learning, sound arts practice, threshold concepts and practices, disciplinary discourses, three-dimensional conceptual mapping and other creative methodologies for developing student meta-, epistemic- and systemic cognition.

Judy Willcocks is Head of the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection (UAL) and an Associate of the Museums Association with twenty years’ experience of working in museums. She has a long-standing interest in developing the use of museum collections to support teaching and learning in higher education and teaches an archiving unit for Central Saint Martins’ MA in Culture, Criticism and Curation. Judy is also interested in developing relationships between universities and museums in the broader sense and is the co-founder for the Arts Council funded Share Academy project, exploring the possibilities of cross-sector partnerships.